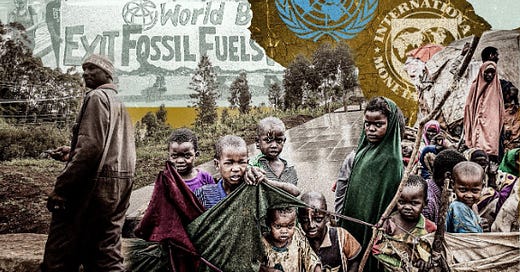

U.N. CLIMATE CHANGE DEMANDS STOP AFRICANS FROM GAINING PROSPERITY

By Cliff Reece

“We have far bigger problems - people sleeping hungry, very poor people around me - I’m more worried about that than I’ll ever be worried about climate change.”

Under a blazing Kenyan sun, elderly women toil on their hands and knees in the reddish-brown clay, separating the choking weeds from the small, green shoots of a finger millet crop. The women are barehanded and barefoot, and they work all day. Clearing a small field takes three days.

“A combine harvester could replace 1,000 people,” Jusper Machogu, an agricultural engineer and farmer in Kenya, told The Epoch Times.

“It makes me sad whenever I see my mom wading through millet. We have women kneeling down and uprooting weeds throughout the farm all day, and it’s sunny. Those machines would change our lives.”

But farmers like Mr. Machogu can’t get a combine harvester. Even if they could afford one from the meagre amount of money they make selling crops, Western nations’ climate policies prevent Africans from achieving what the West already has - modernization and prosperity.

In November 2023, to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuel use, the President of the Republic of Kenya, William Ruto, cut subsidies for fertilizer, fuel, and electricity for the 2023/2024 financial year.

He did so at the behest of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a financial agency of the United Nations (U.N.).

“I come from a community where people use cow dung to fertilize their farms,” Mr. Machogu said. “And the reason for that is because last year, the government of Kenya decided that they were going to listen to what the IMF was telling them. It was telling them to end fertilizer subsidies.

“You can imagine how that’s going to impact farmers. The fertilizer prices went up by almost two times. We have very poor people around here. So, if I was purchasing 20 kilos for my farm, I’m forced to get 10 kilos now.

“Most people have gone back to using cow dung, which is not a good nitrogenous fertilizer for their crop. You can’t compare urea, with a 46% nitrogenous content, to cow dung, with only 4%. It doesn’t make sense.”

Mr. Machogu said the IMF and the Western nations that embrace climate policies for Africa are engaging in neocolonialism, or “climate colonialism.”

And it’s no different than past colonialism, the likes of which liberal elites, such as former US President Barack Obama, have condemned.

“Colonialism skewed Africa’s economy and robbed people of their capacity to shape their own destiny,” President Obama said while in Ethiopia in 2015. “Eventually, liberation movements grew. And 50 years ago, in a great burst of self-determination, Africans rejoiced as foreign flags came down and your national flags went up.”

Two years earlier, in 2013, while in South Africa, President Obama warned a group of young African leaders about the consequences of Africa achieving Western parity.

“If everybody’s raising living standards to the point where everybody’s got a car, and everybody’s got air conditioning, everybody’s got a big house, well, the planet will boil over,” he said, “unless we find new ways of producing energy.”

The new climate colonialism is being driven by global entities such as the U.N., which says Africa should have energy, but due to climate change concerns, it should focus on wind and solar.

Calvin Beisner, founder and president of the Cornwall Alliance, said currently “the most harmful policy” is that the IMF, World Bank, and agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development “refuse to do loans or other funding for coal, natural gas, or oil-based electric generating stations in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia and Latin America.”

It’s particularly damaging in Africa, he said.

Vijay Jayaraj, a research associate for the CO2 Coalition, said he grew up in India and witnessed the growth of India’s industrialization - courtesy of fossil fuels.

“In terms of economic development, energy is the foundational keystone,” he said.

“If you’re going to disrupt how people get energy - where and what quality of energy they receive - it will have an impact. Not just generally, in terms of the economy and the GDP, but also the household and individual level,” Mr. Jayaraj said.

Mr. Machogu criticized the U.N.’s 2023 Sustainable Development Goals for Africa, which he said were developed after U.N. employees went to Africa to study the issues facing the continent. From that expedition, U.N. employees came up with 17 supposed “solutions.”

“They said that one of the problems is climate change,” Mr. Machogu said. “It doesn’t make sense to me because I come from Africa. We have far bigger problems - people sleeping hungry, very poor people around me. I’m more worried about that than I'll ever be worried about climate change.

“Every solution to Africa’s problems is centred around climate change. [The UN says to Africa] ‘If you’re going to end poverty, let’s end it in a way that we don’t impact our climate. If you’re going to have clean water, let’s do it in a way that will not be too bad for the climate.”

He said modern civilization has “four pillars of civilization”—steel, cement, plastic, and fertilizer.

“Without fossil fuels, we can’t produce these four pillars of civilization. Without fossil fuels, we don’t have energy. We must have fossil fuels. It’s how the West beat poverty.”

Mr. Machogu said that the U.N.’s policy boils down to “no fossil fuels for Africa,” which necessarily means no economic progress. Conversely, unrestricted access to fossil fuels could help pull Africa out of poverty.

“Let me speak for Africa because 60% of Africans rely on agriculture for their livelihood,” Mr. Machogu said. “We need fossil fuels for farm machinery.

Despite the fact that the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, and all of these environmental organizations say solar and wind for Africa, we can’t electrify agriculture - if we did electrify, it would be a tiny percent.”

In addition to needing fossil fuels for machines and access to loans to purchase them, Mr. Machogu said expanded irrigation, courtesy of fossil fuels, would benefit Africa.

Holding up a yellow plastic bucket and panning to his surrounding crops, Mr. Machogu said most Africans get water for crops by lugging it from wells. The further your crop is from the well, the more backbreaking and time-consuming the labour.

Mr. Machogu said that unlike in Western civilizations, if profit from agriculture decreases, African farmers can’t simply look for another line of work.

“In Kenya, almost 80 percent of our population is earning a living from agriculture,” he said. So, there is no way we’re going to stop farming.

“And for other people, they cannot even feed themselves [from their farm]. They have to buy food.”

Another Kenyan farmer, Mr. Jayaraj, said he comes from a family of farmers in India. But unlike Africa, India was able to modernize thanks to fossil fuel access - a process that started in the early 1950s and reached completion in 2019 with near-universal household access to electricity.

He said over three decades he witnessed “the socio-economic empowerment of people” in India.

“India’s population is 1.3 billion. And so naturally, it can be taken as a significantly large sample size of what’s happening with the farming sector when you introduce policies against fossil fuels.”

Mr. Jayaraj said more than 500 million people depend directly or indirectly on farming for their livelihood in India.

“When it comes to actual farming, more than 90% of India’s most commonly used fertilizer - called urea - is manufactured in plants that use gas or coal,” he said.

“So, there is no question that if this is impacted, a large portion of the population will suffer not just with their livelihood but also from the subsequent domino effect of food security for the country.”

Mr. Jayaraj explained that in the 1960s, India experienced significant poverty and famine. While these were devastating, they led to an agricultural revolution made possible by the use of fertilizers and fossil fuels.

That experience and the recency of universal access to electricity have given Indians a deep appreciation for reliable energy and the proliferation of coal, oil, and gas.

“India is using a lot of coal. India’s rate of coal consumption is expected to overtake China’s because the power demand rate increase is also expected to be above China’s rate in the coming two decades.

“That sums up the benefit of unabated coal and fossil fuel use, which I’ve experienced over the past three decades.”

He said that, unlike Africa, India is not beholden to Western civilizations and has no intention of switching to or relying on renewable energy such as wind, solar, or electric vehicles

He said that attempting such a switch would be “impractical” and political suicide for anyone pushing such a policy.

Mr. Machogu said that Africa is currently where the United States was in the 1800s. But unlike the United States, Africa isn’t being allowed an industrial revolution.

“In the 1800s, the U.S. had about 80% of the population working in agriculture,” Mr. Machogu said. “Today, we have about the same number of Africans earning a living from agriculture.”

He said that from 1820 to 1920, American farmers took around 10 minutes to produce one kilo of wheat due to lack of machinery. Today, it takes two seconds to make the same amount.

Mr. Machogu said he finds many Western leaders hypocritical.

“These people are consuming lots of fossil fuels - even Obama.

“If you look at Obama’s house, it’s a big, big house without solar panels - the same thing with this other guy, Al Gore.

“Al Gore has got a big, big house. And if you look at his house, he doesn’t have solar panels. So, these people say these things with a hidden agenda,” he said.

“And I think it boils down to Africa not developing and depopulation. Just that. It’s so simple.”

Thanks to Katie Spence at The Epoch Times for her article which has been only slightly amended and added to with Getty Images/ Shutterstock images